Paris-Brest-Paris: So far, so good

To my left there’s a cliff edge with a swirling sea beneath. In front there are hot, buttered crumpets across the road, which I need to swerve to avoid. I glance to my right and I can see a model boat the size of a hedge. I take a deep breath, blink, and realise this can’t be real

It’s 11.45pm on Tuesday and I’ve been cycling since Sunday afternoon. I’m around 30 minutes away from the next control town of Tinteniac. I’m riding through rolling countryside. It’s pitch black apart from my front light shining a bright beam of light ahead. I can see a long line of red taillights stretching into the distance. The air is still. I remind myself that the swirling sea isn’t real, nor is the cliff edge, and the crumpets don’t exist, nor the model boat. They’re the result of long miles in the saddle and little sleep. I’m around 59 hours in to this year’s Paris-Brest-Paris (PBP).

An ABC of PBP

Paris-Brest-Paris (PBP) is a 1,200km self-supported ride from Rambouillet on the outskirts of Paris to Brest in Brittany on France’s Atlantic coast – and back again. It’s the oldest ‘cycling race’ in the world. The first PBP was in 1891, when 400 people entered, 200 started, and 100 finished.

Today around 6,500 enter. It takes place every four years, and participants can choose a time limit of 90, 84 or 80 hours. People ride PBP for many reasons, and riding strategies differ: as fast as possible and barely stopping; or taking almost every second of the 90 hours to enjoy the event. I was nearer the second category. Some have support crews to meet them at intervals but, in the true spirit of audax, most participants take part unsupported.

I’ve been riding audax for over 25 years. This was my fifth Paris-Brest-Paris.

A carnival start

The day before this year’s PBP began, I met up with cyclists from Australia and the USA I’d ridden with before, including on a 1,200km ride in Australia along the Great Ocean Road in 2016. Mark from Seattle was about to start his 58th 1,200km ride; his aim is 60 by the time he’s 60. I’d last seen Sarah from Melbourne when I cheered her into the finish on the 1,400km London-Edinburgh-London ride in 2017. Dan from Wisconsin was very relaxed, having only a general outline for his ride with the control times in mind rather than a strict pre-planning of pace or distance. His approach was similar to mine.

For most riders in the 90-hour category, PBP starts in the late afternoon, when the roads on the outskirts of Paris are quiet. Moments before the start, we were lined up in groups of around 50. The atmosphere was like a carnival. ‘Special velos’ get their own start time. In my starting group were tandemists Kevin and Sue, who live less than 10 miles from me. PBP is an international event but in some ways it’s like a huge Sunday ride with friends.

After a grand countdown, with cowbells and loud cheers, I set off with the two other trikies, Aiden and John. We were soon snaking through the Rambouillet forest in the warm evening sunshine, heading into the first night.

The pace at the start is always brisk, and I reminded myself of the distance ahead. The best thing to do is to settle into a comfortable rhythm. You make this ride successful by adopting a steady pace early on, planning stops with some precision to minimise time spent stationary, mentally focussing only on the distance to the next control, and always remembering it doesn’t matter how fast you’re going. As long as you keep moving, the distance will look after itself. When one pedal pops up you push it down. Then repeat.

Riding to the Atlantic

Day turned into night and I was still riding with fellow trikie John. We took it in turns on the front, sharing the load. It’s rare that two trikes ride together, and it felt good to tuck in behind John, taking an aerodynamic advantage you don’t get when you’re riding with a group of solos.

During this first night we were riding with huge groups of other cyclists – some excitedly chatting, some silent in their concentration. For miles and miles, all you could hear were the sounds of night and the whoosh of tyres on smooth tarmac. We passed pretty French villages buzzing with life well into the early hours. There were shouts of “Bravo!”, the smell and sizzle of sausages on a BBQ, and families with children leaning out of upstairs windows to see the procession go by.

Day two from Villaines to Carhaix was steady and undulating. Having ridden the event before, I knew there was only one real hill – the Roc’h Trevezel into and out of Brest, a 17km climb to an altitude of around 350m. What’s great about ‘the Roc’ is passing people cycling in the opposite direction on the long descent into Brest, different ones on the climb back up afterwards, and the atmosphere at the top.

I arrived at the halfway point in Brest just after 5am on Tuesday morning, crossing the long bridge in the moonlight, the lights of Brest reflecting off the water. I was riding with Stephen from Australia. I’d ridden across the Humber bridge with him on London-Edinburgh-London in 2017, so it felt right to be crossing another bridge together. At the Brest control I sent a text message to my wife Wendy in Rambouillet and my wider family back home: “Ride going great, although a bit windy at times. I’ll be at the finish by early afternoon on Thursday.” A message soon came back from Wendy asking if I was aware that my cut-off time was 11am on Thursday? I’d misread the control closing times and felt very grateful for my virtual support crew!

Trikes together

We’d had a gentle headwind for much of the ride to Brest. The prevailing winds are westerly, which usually means a tailwind home. We didn’t have that luxury this year, with the result that many people struggled to meet the cut-offs and retired. It was shame to see messages from so many of my friends who were unable to continue. The provisional results suggested a 69.2% completion rate, indicating the ‘did not finish’ and ‘finished out of time’ rate was likely to be the highest it’s been for years.

My sleeping and rest strategy for PBP is to have around two-to-three hours’ sleep per night, starting at around 1am. It’s amazing how, once dawn breaks, the body’s circadian rhythm readjusts itself ready for a new day of riding. I met people who book hotels each night, riding fast during the day, and some, like my friend Paul, who survive on five-to-ten minute catnaps for the whole event.

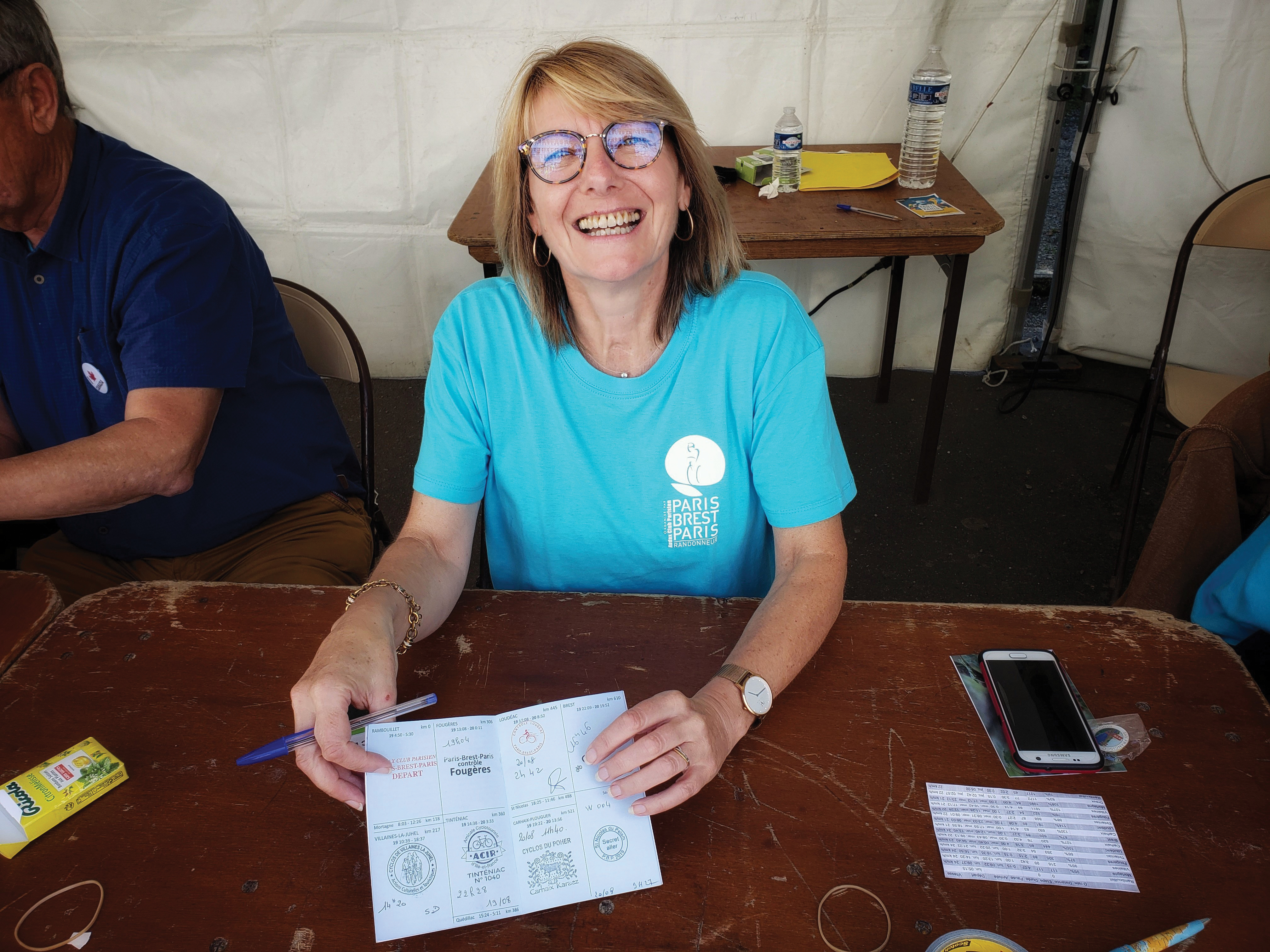

At the Villaines checkpoint on the return journey, local schoolchildren carried our trays of food into a large sports hall. There were 2,500 volunteers in total – people stamping cards, serving food, guiding people to beds, and welcoming riders into checkpoints. Their support is part of what makes PBP the event it is. As I ate, an elderly gentleman came up to me, shook me by the hand, looked me in the eye and said: “Bravo, tu es magnifique!” (Well done, you are magnificent!) Then he moved on to the next person.

I soon caught up with trikie Aiden. We then rode for miles with Bill from Massachusetts in his Breton-themed velomobile. He’d covered it with reflective transfers depicting the Breton flag, which attracted a great reception and loud cheers as we passed through the towns and villages. Seeing that we all had three wheels in common, Bill declared us “a band of brothers from different mothers”.

On my final evening, we climbed up through a forest out into what feels like a wilderness, en route to Dreux, the penultimate control before the finish. As the sun set, the wind dropped and we made faster progress. Everything was aching gently but I knew there was just one more night before I’d be back at the finish. While many people chose to push on, wanting to ride through their final night, I decided to have two hours’ sleep at Dreux. Then I could ride the final 30 miles fresh to fully enjoy it.

The last leg

The final leg on a long-distance ride always conjures up different emotions for me. Part of me wants the ride never to end, part of me wants it to end immediately. Part of me is elated for what I’m about to achieve, part of me feels sad because others I’ve ridden with won’t complete it.

I can generally recall the last few miles into the finish well, and this PBP was no different. The familiar tall trees in the forest, the familiar villages, and then with only a kilometre or two to go, the lights of Rambouillet, the walls of Rambouillet castle, a turn into the grounds, past parked cars, and I could make out a flashing torch in the dark. It was my wife Wendy and my father-in-law Roy, welcoming me into the finish.

I crossed the finish line at 5.05am, having taken 83 hours and 50 minutes to ride 1,228km. One long sweaty hug later from Wendy, I collected my medal.

What stays with you after an event like PBP are those rare moments you capture on the way: the changing landscapes; the sounds of dawn; the view of the setting sun over mountains; the sense of place; the sense of achievement enjoyed and shared with others. While PBP is a cycling event, cyclists are only a small part of it. It’s a proud celebration of the wonderful people of Bretagne, their history and values, and of a tradition that goes back decades. I’ll be back in four years… and I can’t wait.