New evidence highlights the value of cycling to health

The parliamentary debate on cycling last Thursday (16 October 2014) was a wake-up call to government on cycling. The coalition government has been floundering, with a botched timeline for release of their Cycling Delivery plan. In a dramatic and unexpected move, this was finally released just hours before the debate began.

The report is weak, falling far short of the £10 per head we need and lacks substance in a number of other areas. Cross-party heartfelt and articulate support was given for the proposal of the Get Britain Cycling report for at least £10 per person. As a Times editorial points out, this amounts to only 3% of the transport budget. With health, environment and congestion savings, it would almost instantly pay for itself.

Research by myself and James Woodcock, commissioned for early release by the CTC, was mentioned several times in the debate. The details of the report were designed to arrive at a simple outcome: quantifying the benefits of cycling in the long term. Using World Health Organisation recommendations these were found to be in the billions for health alone. The next step for the research is to identify other benefits. But what about the big picture – what does this research area mean for policy?

The next step for cycle campaigners is clear: lobbying politicians at all levels so that the 'cyclist vote' (in reality, the pedestrian, elderly and young adult vote too – as we shall see) is heard loud and clear. As a publicly funded academic, my role in the debate is to provide evidence. In the era of 'evidence based policy', a condensed nugget of hard evidence on the matter can be worth reams of rhetoric. As a point of departure, it is worth seeing what evidence was used in the debate and other areas where data can inform the debate.

We want 10% of journeys to be made by bike by 2025—the figure was less than 2% in 2011—and we call for lower speed limits in urban areas. We want more effective enforcement of the law, we want children to be taught to ride at school, we want more segregated cycle lanes, and we want cycling to be considered properly as part of the urban planning process. We also call for top-level, committed leadership, because cross-departmental collaboration is essential if we are to improve cycling conditions in Britain.”

Ian Austin MP

Dudley North

Ian Austin commenced the debate replying to Mr Goodwill's plan by setting out clearly what we want for cycling. Never again let it be said that active travel advocates don't know what they want: his is a good a summary as any of what is being called for, by a broad coalition of NGOs and civil society, from the CTC to the AA.

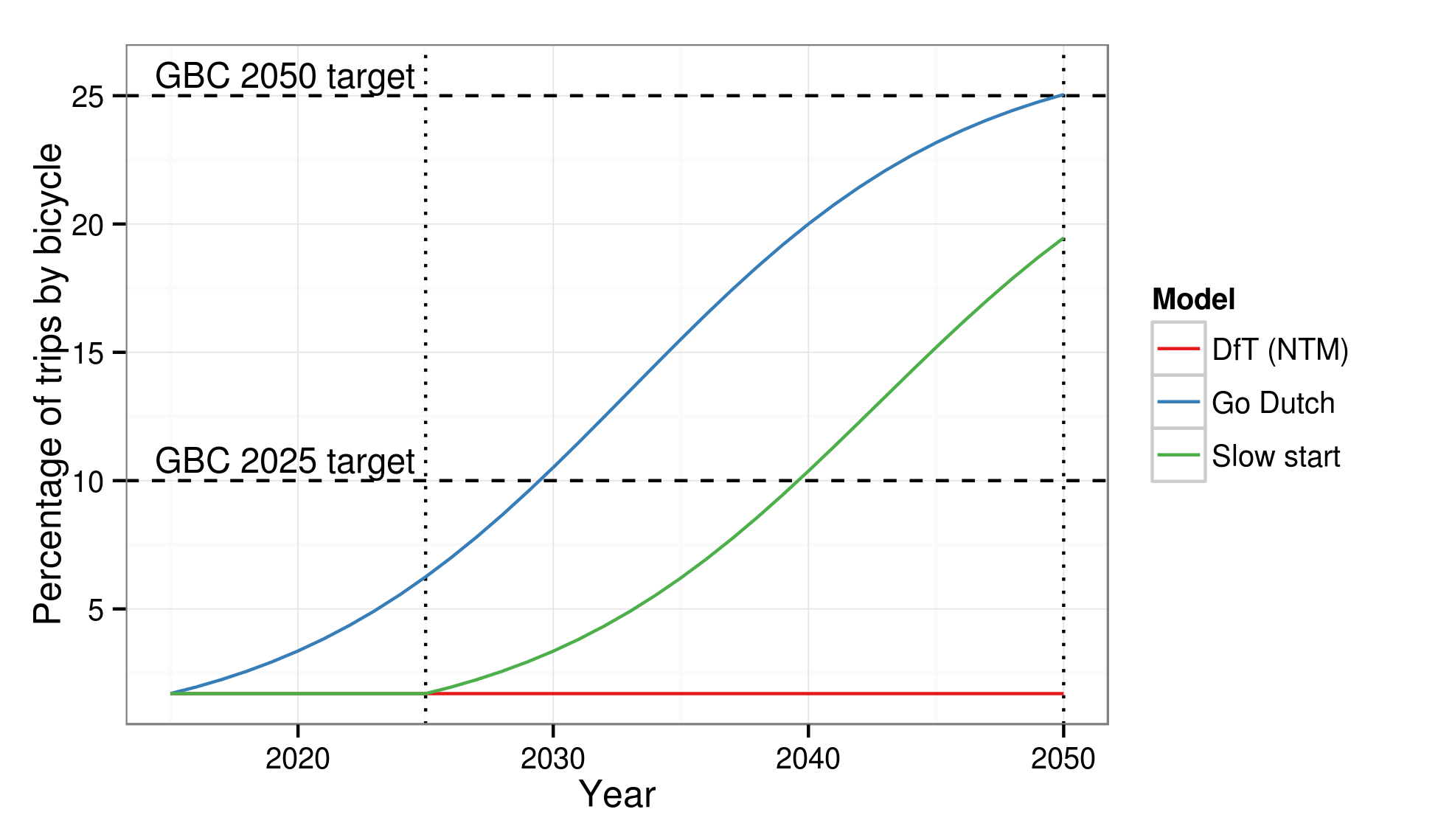

Returning the evidence, simple mathematics shows that the '10% by 2025' target is highly ambitious in the context of the longer term '25% by 2050' target. The former implies a growth rate of 0.8 percentage points per year (from 2 to 10% - 8% in 10 years) while the latter implies a lower growth rate of 2/3 of a percentage point per year (figure 1). So the GBC report recommends front loading the uptake of cycling which certainly is possible but not easy to model.

An additional issue with the above numbers is that we do not live in a linear world. Population ecology shows us that growth rates are often curvey (typically following some kind of S-shaped curve) and sometimes abrupt: "history teaches us that transport modes don't just evolve, but can flip, and usually in the most unexpected ways" as Rachel Aldred put it, quoting Carlton Reid.

In my research with James Woodcock, we translated this into a 'logistic function' of cycling over time. This top-down approach builds on my previous research with projected the cycling rate in Sheffield to 2025. Now, applying the principle to the nation and to 2050, the modelling challenge was harder, but the principles are the same (see figure 1).

As is clear from the figure, we did not just select one future and stick to it: different scenarios reflect different possibilities for change. More importantly, the clearly defined timeline – and the curves could be set to any shape, I would advocate a more front-loaded functional form – allows for annual targets. Saying 'by 2025' allows politicians to kick the issue into the long grass. With annually released surveys such as the National Travel Survey (NTS), we could hold politicians to higher and more specific targets to see if we are on track or not.

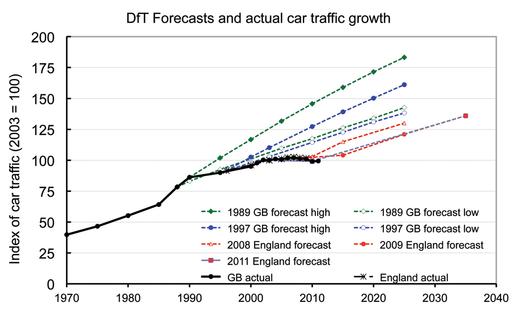

This approach differs strikingly from the Department for Travel's 'predict and provide' approach, where each year increased driving is predicted (Figure 2). This comes despite real-time evidence of reduced car use and longer-term signs that we may be at or approaching the era of 'peak car'.

It is only with a clearly defined vision of the future, contained in a transparent and reproducible model that we can properly plan for an obviously uncertain future. Preferably this plan should be available to the public for testing with open source software (The Department of Energy and Climate Change's 2050 planning tool provides an excellent example of this).

With such a vision in place, planning for the provision for active travel, and understanding of the benefits it brings, can take place in an orderly way. This differs greatly from the government’s current approach on cycling which is “sporadic and episodic”, lurching from one scheme to the next.

This is an amended article that first appeared on The Conversation.