Road safety must target most dangerous, not the least safe

What’s the best strategy to improve road safety in Scotland? Should we focus on making the most vulnerable people safer, or put efforts into reducing the greatest dangers? These are questions I have been considering as I put together Cycling UK’s response to the Scotland Road Safety Framework to 2030 consultation.

When the clocks go back at the end of October, there are often well-meaning information campaigns saying something like ‘Now that it’s getting dark earlier, remember your cycle lights and wear hi-viz to be seen’. These campaigns often elicit a response from cyclists on social media of ‘stop the victim blaming - you should be reminding drivers to look out for cyclists’.

These campaigns are an example of focussing on the most vulnerable and finding ways to make them safer – in this case brighter and more visible. Using lights is a legal requirement, but the real danger here is not the cyclist, but drivers not paying attention. Being lit up like a Christmas tree won’t help if a driver isn’t focused on the road.

This regular focus on the cyclist being the one needing to take action can give the impression that cyclists who aren’t in high vis are behaving in a risky manner, or irresponsibly. It also tends to imprint on people’s minds that cycling is unsafe and dangerous.

Cycling itself isn’t dangerous – it causes very little danger to other road users.

Another very familiar road safety campaign is the pre-Christmas don’t drink and drive message. Hard hitting TV campaigns, strong enforcement and breathalysing motorists suspected of drinking has made drink driving socially unacceptable.

We all know drink driving is dangerous, but can you imagine a pre-Christmas campaign which said, ‘Beware of the drink driver this Christmas – if you have to drive, wrap Christmas lights round your car so a drunk can see you better’. This is clearly an absurd example, but I’m using it to make an important point: we need a consistent focus on reducing danger, not on making the most vulnerable safer.

Cars are involved in 84% of collisions in Scotland where cyclists are injured – it is 76% where a pedestrian is injured. A recent report by a Westminster Parliamentary Committee shows similar results for cars but looks further into the data to find out what mode of transport presents the greatest danger per mile travelled.

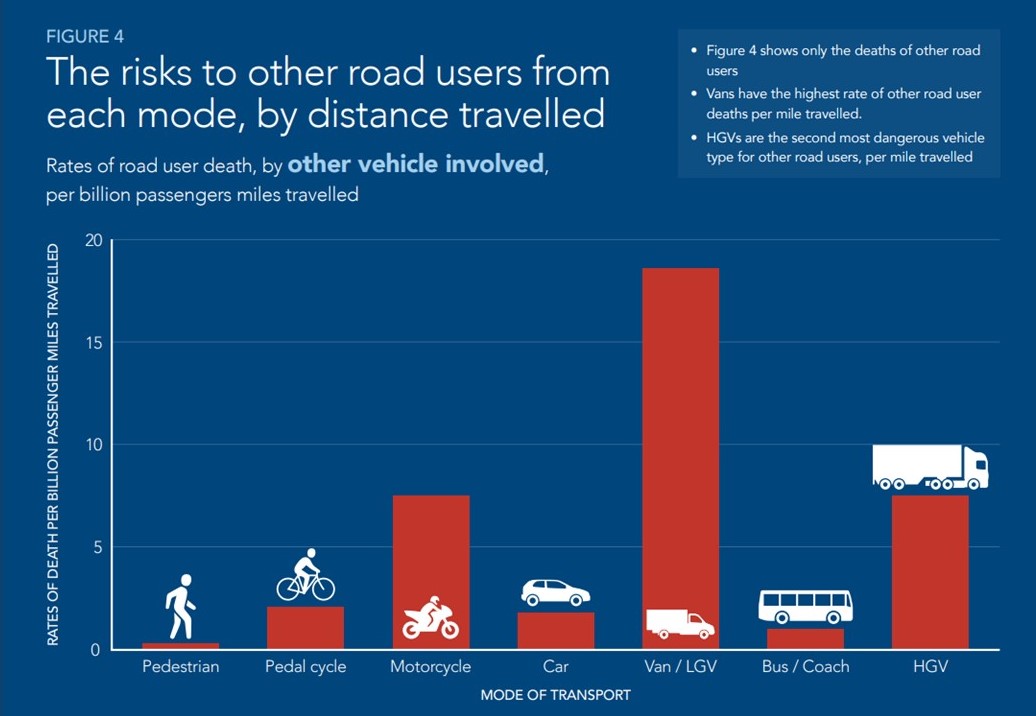

The graph reproduced below shows clearly that vans, light goods vehicles (LGVs) and heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) present the greatest risk to other road users. It’s relatively safe to drive one of these vehicles, but they pose the greatest danger to others.

A danger reduction approach to road safety policymaking might use these findings to ban HGVs and vans from streets near schools within certain hours, or prevent HGVs using busy high streets and residential streets.

If we take a road danger reduction approach to road safety, would we need cycle lanes at all? Not if we removed all the danger - but that’s not really practical.

We still need buses on the roads, and cars, lorries and vans aren’t going away anytime soon. Separated cycle lanes are needed to reduce the danger posed by other forms of transport, especially on fast busy roads.

Residential streets can have the danger to cyclists and pedestrians reduced by setting the speed limit to 20mph, creating low traffic neighbourhoods, and redesigning the streets to be attractive to people rather than for motor vehicles.

The point is that we need to re-dress the balance of how we think about and do road safety awareness raising and policymaking, towards working out what are the greatest dangers and reducing them. If we do this we can make streets safer, prove they are safer, and achieve the ambitious targets proposed in the Road Safety Framework. We can also stop reinforcing a false message that cycling is dangerous.

Instead, we have a real chance of encouraging more people to ride and be physically active with the health benefits to the population that will far outweigh the dangers of the roads.

Read more in our response to the Road Safety Framework consultation, and thank you to all our members and supporters who made their voices heard using our guide.