Why do cyclists need safer lorries?

The risk HGVs pose to cyclists

HGVs (i.e. goods vehicles over 3.5 tonnes) pose a disproportionate risk to both pedestrians and cyclists. On average each year between 2012 and 2016, they:

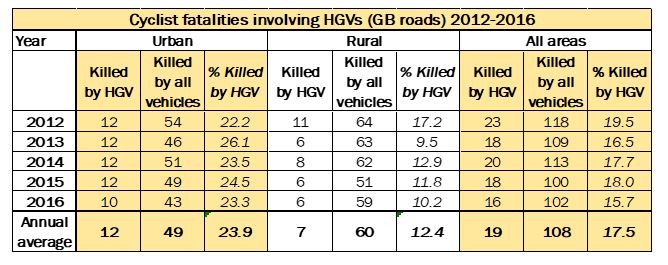

- Accounted for only around 3.6% of non-motorway motor traffic mileage on British roads, but were involved in 17.5% of cyclist fatalities;

- Were involved in almost 14% of pedestrian fatalities;

- Accounted for around 2% of urban and 5% of rural motor traffic, but were involved in almost a quarter of cyclist urban fatalities and just over 12% of cyclist rural fatalities.

Cyclists’ collisions with HGVs are also far more likely to prove fatal than those involving cars: the cyclist is killed in about a fifth of serious injury cyclist/HGV collisions, compared with around 2% for cyclists/car collisions.

Most of the collisions between cyclists and HGVs occur during lorry manoeuvres and /or at junctions, with the most serious risk to pedestrians and cyclists coming from the largest, heaviest vehicles that seat the driver high up and provide only limited ‘direct vision’ from the cab. This is especially the case with HGVs used on off-road sites.

‘Direct vision’ and vehicle design

‘Direct vision’ refers to a driver’s ability to see what is going on outside their cab without using the indirect means of mirrors or cameras: it is what the driver can see directly. Obviously, this is crucial for cyclists and pedestrians who share the roads with lorries and are disproportionately at risk from their manoeuvres.

Yet, while our urban environment has changed dramatically in the last twenty years, with many more cyclists in London for example, the basic HGV cab has hardly altered since the 1970s.

Their design has been dictated by their chief operating purpose and commercial viability. For instance, contractors working on landfill, construction or quarry sites favour vehicles with a high ground clearance able to cope with the terrain, even though they often spend only a tiny amount of their time in off-road conditions – about 2% of it in London. These vehicles (N3Gs), however, afford their drivers a limited direct view from the cab, and consequently present a particular threat to pedestrians and cyclists.

Accordingly, the primary issue to address when reducing lorry danger is cab design, and whether HGVs with cabs that do not meet a set standard for direct vision should be permitted to operate in urban areas.

Clearly, this is essential if we want to encourage more people to cycle in the busiest urban areas, and for cycling and walking to be universally seen as easy, fun and safe.

A Direct Vision Standard

Cycling UK believes the Government should introduce a national ‘direct vision standard’ (DVS) for HGVs, to enable lorry permit schemes, modelled on the scheme being introduced in London (see below), to be adopted in urban areas throughout the country.

Proposals in London

In 2016, the London Mayor announced plans to assess construction and other HGVs using a world-first DVS, supported by a safety permit scheme.

Informed by collision research, DVS is a proposed five-star rating standard based on how much a driver can see of the area outside where vulnerable road users (VRUs) are most risk.

If approved, the scheme will apply to all large HGVs over 12 tonnes (N3 Class) working in or entering Greater London from 2020.

HGVs will be given a rating of between ‘zero-star’ (lowest) and ‘five-star’ (highest). Only those vehicles rated ‘one-star’ and above would be allowed to enter or operate in London from 2020. Zero-rated vehicles would only be allowed if they can prove compliance through safe system measures.

By 2024, only ‘three-star’ rated HGVs and above would automatically be given a safety permit.

HGVs rated ‘two-star’ and below would need to demonstrate increased safety through progressive safe system measures.

The evidence

The scheme is being introduced because evidence shows that the amount an HGV driver can directly see through the cab’s windows plays a major role in collisions with vulnerable road users.

Whilst it is not possible to retrospectively determine with certainty whether or not a particular HGV collision with a cyclist or pedestrian would have been avoided if the driver’s direct vision from the cab had been better, various studies carried out by TRL, Leeds University, Loughborough University and TfL indicate, for example, that:

- In collision with HGVs between 2009 and 2014, 61% of cyclist and 49% of pedestrian fatalities were potentially influenced by the vehicle’s blind spots;

- Drivers relying on mirrors rather than direct vision take on average 0.7 seconds longer to observe potential hazards around their cab. This equates to a travel distance of 1.5 metres at 5 mph;

- Mirrors do not provide the comprehensive coverage of the area which is directly visible from a ‘five-star’ direct vision HGV;

- In simulated potential HGV collisions with a pedestrian, 23% more participant drivers collided with a pedestrian in standard cabs compared to low entry cabs (LEC) with improved direct vision.

Not surprisingly, the introduction of a DVS enjoys substantial support. TfL’s first consultation on it revealed that:

- 84% of respondents agreed that adopting a DVS had the potential to reduce road danger;

- 78% of respondents agreed that lorries with the worst DVS should be excluded for London.

Construction-type vehicles, such as tippers and skip-loaders, are over-represented in crashes with cyclists, but other types of HGVs are also involved.

Modern designs

It is important to note that LEC HGVs with significantly improved direct vision are already in use and on the market.

Mercedes and Denis Eagle, for example, have adapted their refuse lorries for construction use, offering a variety of mixer, tipper, tractor unit and other bodies / cabs for purchase.

Also, the benefits of LEC and improved direct vision have long been recognised within the refuse sector, where such designs are now the norm.

To sum up, it cannot be stressed enough that:

- The casualty statistics clearly show that HGVs present a disproportionate risk to VRUs, particularly in London;

- The research identifies a solution, through improved direct vision from the cab;

- Vehicles providing improved direct vision are already on the market, but we have yet to see a wide uptake, and they are far from the norm.

Costs

Unfortunately, some elements of the freight industry are opposed to the safety permit scheme because of the financial outlay involved in transitioning their fleets.

Cycling UK, though, is sceptical about such arguments because they overlook the economic and other costs to business of collisions and fatalities, and the benefits of improved safety performance.

An HGV operator involved in a fatal collision will potentially:

- Sustain reputational damage;

- Lose business;

- Face increased insurance costs;

- Incur legal costs;

- Expend considerable management time dealing with the consequences;

- Face prosecution / civil proceedings;

- Have to address work practices after the event.

In short, improving work-related road safety makes business as well as road safety sense.

Diluting the Direct Vision Standard

Cycling UK supports both the DVS and the concept of a ‘safe system’ approach, but agrees with TfL’s proposals to base the star-rating system purely on the vehicle’s direct vision, rather than combining the DVS and ‘safe system’ so that the star ratings relate to the overall safety of the vehicle.

Quite reasonably, though, TfL is considering a safety permit scheme whereby responsible operators, who have invested in other safety equipment such as cameras, sensors, under-run protection etc., can demonstrate a ‘safe system’ in lieu of their vehicle passing the DVS star-rated standard.

If the DVS and safe system approach are merged into an overall star-rating system, however, the certainty and objectivity of the DVS will be compromised. After all, the assessment of a HGV’s DVS will involve an empirical calculation of the actual field of vision from a particular position in the cab. Subject, of course, to accurate measurement, it will be a calculation which yields a definitive and objective answer.

The certainty offered by a DVS-only star-rating system offers substantial advantages. For example:

- An operator will know the specific rating of any vehicle they purchase - if that is a ‘three-star’, they will know the vehicle will still automatically obtain a permit in 2024;

- It gives those whose vehicles fail the objective DVS test the chance to present a case for a permit based on a safe system instead.

Merging these concepts (i.e. DVS + safe system approach) into an overall star-rating, however, would merely introduce uncertainty. Potentially, this could lead to vehicles moving in and out of bands dependent on which camera system they have at a particular time, whether driver training is still being offered etc.

As the current vehicle fleet is progressively replaced, direct vision cabs need to become the norm, with sensors, cameras, driver training etc. providing additional benefits, rather than being seen as alternatives to direct vision.

In conclusion:

- HGV cabs should be designed so that drivers can see pedestrians and cyclists directly through their windows (in the same way that most bus drivers can).

- Extending the glass in cab doors and windows as far as possible helps improve the driver’s direct view of cyclists and pedestrians nearby. Along with more glass, lower driving seats bring the driver personally closer to the level of other road users, again making it easier to see VRUs, and anticipate and react to their movements.

- There may be benefits from fitting indirect vision devices (cameras, mirrors and sensors), but they are no substitute for direct vision and designing out ‘blind-spots’ altogether.

The research evidence, as discussed above, is clear: improved DVS has road safety benefits, particularly for people walking and cycling.

Reducing the demand for HGV movements in urban areas

Cycling UK wants to see national and local government take steps to help reduce the demand for HGV movements in urban areas, and at the busiest times, with part of the solution being through the promotion of cargo bikes.

Cycling UK implicitly recognises that banning all HGVs from every urban area for the sake of cycle safety is not feasible. This is why we support a system that would refuse HGVs with inadequate DVS a safety permit unless further safety measures are implemented (see above).

The Government and local authorities, however, could and should do more to help reduce the demand for HGV movements in urban areas.

Routing

Operators can minimise risk by routing HGVs away from roads and streets that are busy with cyclists, pedestrians and community activity.

Digital mapping tools can help facilitate this and, if such lorry route networks are clearly signed, other road users can also choose to avoid them.

Out-of-hours/night-time only deliveries

Despite the safety benefit for cyclists and pedestrians if deliveries are made outside the rush hour, residents and communities often object because of the disturbance caused, particularly at night. It is not just the sound a lorry makes whilst driving that causes problems - unloading noise can be an issue too. As a result, some councils restrict delivery activity at certain times.

Limited permit schemes, promoting the use of smaller goods vehicles and evening-only deliveries to shops in residential areas may, for instance, help allay residents’ concerns.

Also, distribution centres away from residential areas should also be able to receive deliveries at night, with the goods being transferred to smaller vehicles and sent on at less unsociable times.

Cycling UK supports night-time and out-of-hours deliveries, but only if:

- Restrictions are also applied at busier times;

- The vehicles involved are designed with cycle safety in mind;

- Residents’ quality of life is safeguarded.

Distribution centres

Encouraging the location of distribution centres on the periphery of urban areas would enable HGVs to transfer their loads onto smaller vehicles (including electric lorries and cargo bikes) for delivery further into the town or city.

Not only could this improve safety for VRUs, but also improve efficiency for freight operators, as congestion and the infrastructure typical of many urban areas are often a challenge for HGV drivers to negotiate (e.g. roundabouts that cannot cater for their vehicle’s turning circle).

Action from big customers

Large establishments, including local authorities and government-funded companies, should also get involved in schemes to reduce the number of freight vehicles delivering to them. A good example is Newcastle University’s ‘urban consolidation trial’, which focuses on electric vehicles.

Cargo bikes and other alternatives to HGVs

As an alternative to larger vehicles, freight (cargo) cycles are an efficient and environmentally sound way of transporting and delivering loads in urban areas, helping to reduce the number of lorries and vans on the road, and the hazards and congestion they cause.

A report from CycleLogistics (an EU project to promote cargo cycles) calculated that, potentially, 42% of all motorised trips for goods transportation in European cities could be shifted to cycles.

As no legal weight limit applies to the load carried by any cycle, the deciding factors are the machine’s specification and the ability of the rider to propel it. With electric assist, loads of up to 300 kilos can be delivered.

Cycling UK welcomes the Government’s plans to provide financial support for the uptake of cargo bikes.

We are also encouraging the Government to overturn a suggestion from the European Commission that riders of e-bikes (including electrically assisted freight bikes) must have compulsory insurance. There is no justification for treating e-bikes as being more hazardous than equivalent conventional bikes, given that the weight and power limits for e-bikes are set to avert this risk.

Increasing the volume of goods transported by river is also a viable option for many cities, as is rail. This offers both road safety and air quality benefits.

Research for the Campaign for Better Transport found that removing just 2,000 lorries a day from four specific roads would result in a 10% reduction in NOx and a 7% reduction in particulates from all road traffic in each of the four routes studied, with a 2.5% reduction in carbon emission across all four routes.

Regulation by local authorities

Whilst the measures outlined above can help reduce the demand for HGV movements in urban areas, local authorities could and should make greater use of their powers to regulate HGV traffic.

Under the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, local authorities can introduce lorry control measures such as weight and loading restrictions or restrictions/prohibitions on movements by vehicles of certain widths, heights and weights, in certain streets/areas, at certain times of day etc.

Equally, when granting planning permission for development or infrastructure projects, local authorities should be mindful of the lorry movements the site is likely to generate during construction (and/or after construction if the site is a depot).

Through planning permission and Section 106 (S.106) agreements, Cycling UK therefore recommends that local authorities should:

- Oblige all operators to use vehicles designed to comply with DVS and conform to the CLoCS (Cycle Logisitics and Community Safety) standard (see below);

- Stipulate the routes lorries must take;

- Require that construction sites are suitable for vehicles fitted with safety features (e.g.: sideguards);

- Insist that all drivers are given cycle awareness training.

Of course, it would be local authorities who impose such conditions or S.106 agreements, but it's important that national government encourage this through planning guidance.

Both national and local government can also support the adoption of lorry safety standards through the procurement of public contracts. Examples include the HS2 rail project, highway construction work and refuse disposal contracts.

Construction Logistics and Community Safety standard (CLoCS)

CLoCS (Construction Logistics and Community Safety) standard should be adopted as a national standard for safer lorry equipment, driver training and fleet management.

Drawing on best practice, CLoCS is a common standard designed to protect vulnerable road users from the risks posed by HGVs, specifically on construction projects, and is implemented by construction clients through contracts.

One of CLoCS’ strengths is that it has been developed through collaboration between construction clients, logistic operators and industry associations, and therefore enjoys a significant level of support.

Also, it covers the role of the contracting client (i.e. the developer), as well as the construction and/or delivery companies undertaking work for them.

It sets detailed minimum requirements covering:

- Quality operations;

- Collision reporting;

- Traffic routing;

- Vehicle blind-spot minimisation;

- Warning signage;

- Under-run protection (sideguards);

- Vehicle manoeuvring warnings;

- Training and development;

- Driver licensing.

CLoCS grew out of lorry safety commitments made by TfL and Crossrail Limited during the passing of the Crossrail Bill (now the Crossrail Act), following a petition by Cycling UK.

As noted above, Cycling UK now recommends that the Government supports it as a national standard for all construction lorry operations.

This would help ensure that local authorities, other public sector bodies and all other organisations who contract such services are able to identify operators who abide by the highest safety standard, and specify CLoCS and the national Direct Vision Standard (once agreed) as conditions for planning permission, or S.106 agreements.

Importantly for the construction industry, which is understandably resistant to different standards being set by different city authorities around the UK, a national standard would ensure that the same standards applied everywhere.

Finally, the work-related risk requirements identified through CLoCS are also a good model for HGV contractors working in other fields (e.g. refuse collecting) to adapt to promote VRU safety and reduce risk.