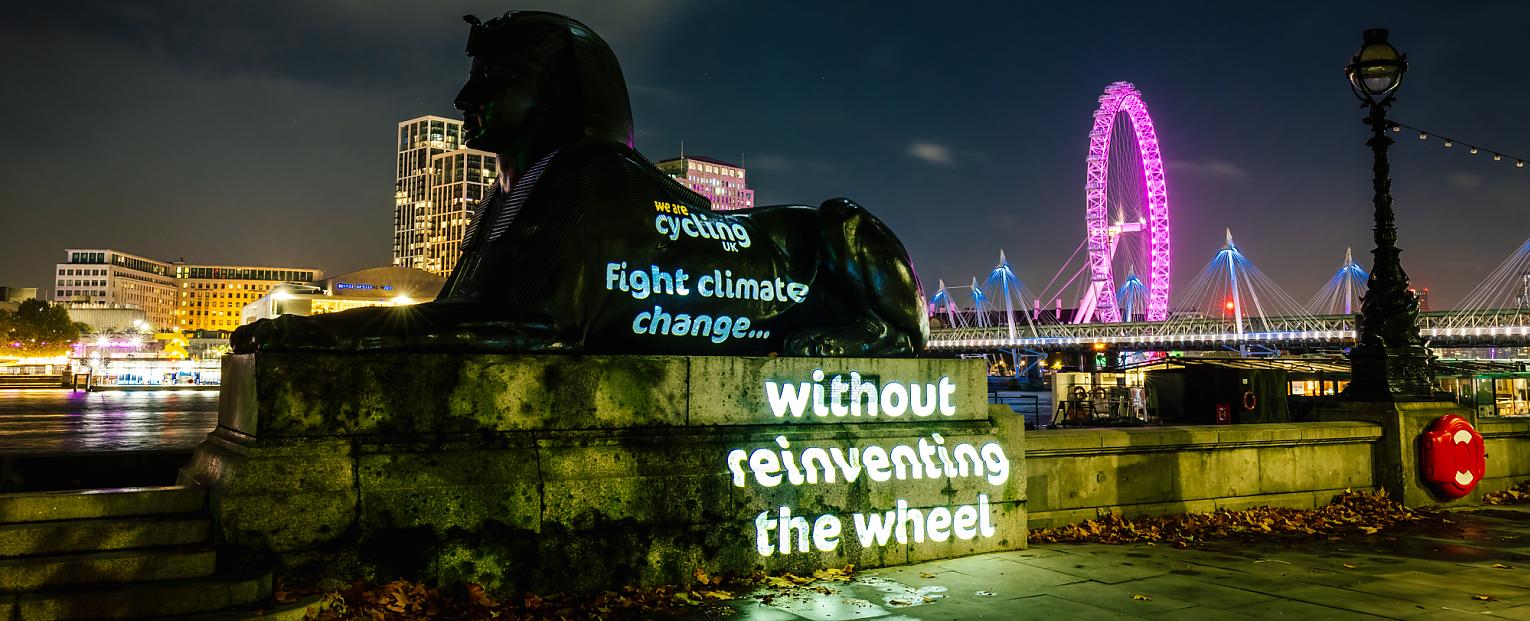

Is it a 'Transport Decarbonisation Plan' or just a plan for electric traffic jams?

Last March, Grant Shapps launched the process leading up to today's Transport Decarbonisation Plan (TDP), by issuing a document entitled 'Decarbonising Transport: setting the challenge.'

In his ministerial foreword to 'Decarbonising Transport', Shapps set out his bold vision of a net-zero transport future, in which "Public transport and active travel will be the natural first choice for our daily activities. We will use our cars less."

It was a bold, inspiring statement, and I and others gave him huge credit for it. This was the first time that a UK Transport Minister had dared to talk about traffic reduction since John Prescott tried (but sadly failed) to reduce road traffic in the late 1990s.

It seemed that Shapps had fully understood the ever growing evidence-base, showing that decarbonising surface transport cannot just involve replacing petrol and diesel vehicles with electric vehicles. For a whole host of reasons, we need fewer cars, not just newer cars.

The need for evidence-based targets and funding allocations

However, I also said at the time that this vision would need to be backed up by evidence-based targets, and evidence-based policies and funding allocations to meet those targets. Cycling UK then spelled out what policies were needed in our response to 'Decarbonising Transport' (see summary). Meanwhile, our evidence last autumn to the Treasury's Spending Review (see blog) set out the funding allocations that were (and still are) needed if the Government is to meet its current targets to double cycling and increase walking.

In short, we said that the Government needed to set targets to halt and reverse the growth of road traffic, at a rate that was consistent with its wider 'net zero' targets to decarbonise the economy by 2050. Traffic-reduction targets should also reflect the need to tackle the crises of air pollution, road danger, inactivity-related ill-health and 'level up' access to transport and travel opportunities. A car-dependent transport system is one that prevents children - as well as many older, disabled or less-well-off people - from getting around safely on their own.

Having worked out what proportion of private motor-vehicle trips (or miles) would need to be shifted to something else (walking, cycling, public or shared transport, some combination of these, or simply not travelling at all), the Government could then set corresponding targets for these sustainable alternatives. And then allocate funding according to what was needed to meet those targets. The traffic reduction targets, the associated sustainable transport targets and the resulting funding allocations would all rest on a solid evidence base - that would actually be a transport strategy!

Yet last week, I marked the 25th anniversary of the Government's first National Cycling Strategy (published 10 July 1996) by contrasting this with the habit of plucking targets out of thin air, and then failing to allocate the money needed to meet them.

Unfortunately, evidence-based targets and funding allocations are the critical missing ingredients from the TDP. If Grant Shapps really wants local authorities and others to play their part in realising his vision of a world in which "We will use our cars less", he needs to start by spelling out how much less, and by when - and then allocate funding accordingly.

The good (and potentially good) bits

Despite these fundamental weaknesses, there are quite a few good or potentially good things in the TDP. Here is a quick overview of some key positives:

Commitment to "deliver a world class cycling and walking network in England by 2040" (pp52-62, especially p58)

This is a new commitment, and a very welcome one. The fact that it has a deadline (the year 2040) means we can also estimate how much funding needs to be spent over that time-period to achieve cycling and walking networks which are as well-designed and as comprehensive as those in countries like the Netherlands.

The TDP also restates a previous Government commitment to spend £2bn over 5 years towards meeting this goal. In one respect, that is reassuring. There was (and still is) a risk that the Treasury could try to claw back some of the £2bn in its Spending Review this autumn - claiming that local authorities lack the capacity to spend this amount of money (or to spend it well). Unfortunately, this is a circular argument - given that the Treasury's spending allocation for cycling and walking acually went backwards this year, rather than ramping up to achieve the £400m annual average implied by the promise of £2bn over 5 years.

My overall impression of the TDP is that ministers still want to assure the public that they can carry on driving, when the evidence clearly shows that this simply isn't compatible with the urgency of the climate crisis

Roger Geffen MBE, Cycling UK's policy director

We have to avoid a Catch-22 situation where councils can't prove they can spend the money - so the Treasury doesn't given them any - hence they never develop the capacity to spend this much money, let alone prove that they are able to. Between now and the Spending Review, it is now crucial that we support local councils in drawing up ambitious local cycling and walking network plans, to help them (and us) prove that local authorities can, and must, be given at least £2bn that was promised, but probably something more like the £6-8bn that is apparently needed according to DfT's own supressed evidence.

Addressing cycle safety concerns and the negative perceptions of cycling and cyclists (p193)

It is a perennial call from cycling advocates for the Government to do more to address cyclists' safety concerns, to address negative public perceptions of cycling and cyclists, and to raise driver awareness of cycle safety. There is also a great opportunity do so when the new Highway Code rules it consulted on last year are (hopefully) adopted later this year.

Cycle-rail commitments (p81)

The Government had already made some useful commitments on cycle-rail integration in last year's 'Gear Change' cycling and walking vision document (see p25) and the more recent 'Rail White Paper' (aka the Shapps-Williams review - see pp72-73 and 89). However the TDP goes further, promising that "We will increase the amount of space for bikes on trains wherever practically possible, particularly on popular leisure routes, and will make it easier to reserve bike spaces online and without reservations on emptier trains. All future trains will include more bike space relevant to the markets served."

Public, electric, adapted and cargo cycles, and 'try-before-you-buy' schemes (pp56-57, 80, 132, 138-140 and 193)

There is plenty of emphasis on public hire-bikes, electric cycles, cargo-bikes and non-standard cycles (cycles which are adapted for use by people with disabilities), and a recognition of their potential to incease the distances that people can cycle, to broaden the demographic range of cycle users, and to boost the role of cargo-bikes in decarbonising 'last mile' deliveries. It has been widely trailed that the "further announcements on cycling and walking" later this summer (promised on p60) are likely to feature significant new support for e-bikes.

Cycling UK is strongly supportive of these developments, likewise the opportunities to offer people these various non-standard cycles on a 'try before you buy' basis. 'Try-before-you-buy' is particularly important for older or disabled people and those with health conditions, who potentially have a huge amount to gain from taking up cycling, but who may need a particularly expensive form of cycle to enable them to do so. So they really need an opportunity to try it out for a while first, before making a very significant outlay that they would otherwise really struggle to justify.

A faint hint of some traffic reduction targets! (p6)

Although I have lamented the lack of clear targets to decarbonise transport and reduce traffic, there is some text buried away on page 6 which says: "We want to reduce urban road traffic overall. Improvements to public transport, walking and cycling, promoting ridesharing and higher car occupancy, and the changes in commuting, shopping and business travel accelerated by the pandemic, also offer the opportunity for a reduction or at least a stabilisation, in traffic more widely. That will benefit everyone, drivers included." You couldn't quite describe this passage as setting targets to reduce urban road traffic and at least to stabilise road traffic overall, but it comes tantalisingly close! We'll certainly want to press the Government to let itself be held to account for these laudible aims.

Integration of cycling into local transport planning (pp38 and 151-156)

The TDP promises to make decarbonisation a significant element of a revived process of Local Transport Plans (LTPs) and associated funding arrangements, with walking and cycling being at the heart of this process. This could act as a really powerful incentive for local authorities to develop ambitious and genuinely comprehensive local cycling and walking network plans - or else risk not getting funding for other elements of their LTPs.

If the Government is serious about its aims to reduce urban road traffic and at least to stabilise it overall (see above), it could greatly boost its chances of success by using existing powers under the Road Traffic Reduction Act 1997, to issue guidance to local authorities on setting local traffic reduction targets that are in line with these national ambitions.

Planning (pp156-160)

My colleague Duncan Dollimore and I have repeatedly expressed concerns in recent months that the Government's Planning White Paper risks perpetuating car-dependent new housing and other developments. Encouragingly, the TDP addresses these concerns head on, making some really encouraging promises about ensuring they support cycling and other forms of sustainable transport. I just hope that Ministers in the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government are also fully signed up to these commitments.

Increasing vehicle occupancy, car-sharing, a sustainable travel reward scheme and "commute zero" (pp181-184 and 189-191)

Although car-sharing doesn't specifically relate to cycling, the notion of having access to a car without needing to own one is an idea whose time has come - and the TDP is encouragingly positive about it. Not only does it save people the fixed costs of owning a car (including insurance), but it also creates a cost incentive which favours walking, cycle or using public transport for trips which don't require a car. Cycling UK will certainly want to talk to the Government about the role of our Cycle Friendly Employers scheme as part of the Government's sustainable travel award and "Commute zero" initiatives, to incentivise individuals and employers alike to embrace low-carbon travel . And the idea of increasing average vehicle occupancy also has non-obvious implications for the following section of the TDP I've summarised.

Reforming transport appraisal and revising the 'National Networks' National Policy Statement (pp102-103 and 161-162)

These will appear to be abstract and arcane points, but they may be crucial. National Policy Statements (NPSs) are documents which effectively alllow ministers to give themselves planning permission for 'Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects' (NSIPs), and the 'National Networks' NPS (NN-NPS) does this specifically for road and rail schemes. However, it was written in 2014, before the Government signed up to the Paris Accord or adopted its current 'net zero' target.

There is a lot of pressure on Government to rethink its £27bn Roads Investment Strategy (RIS2), for environmental, economic and indeed legal reasons. Our friends at the Transport Action Network (TAN) are leading the charge, by bringing two legal challenges - one of which is to RIS2 itself, the other being to the Government's refusal to revise the NN-NPS which underpins it. The TDP finally promises to revise the NN-NPS, meaning that TAN have effectively won their 2nd legal challenge.

Unfortunately, revising the NN-NPS won't stop any road-building in the short term, as it will take around 2 years to draw up a replacement NPS. Therefore TAN still need to win their 1st legal challenge, in order to get some of that anachronistic £27bn roads budget reallocated for walking, cycling and public or shared transport. The court hearing took place last month, though it could be weeks or months before we know the outcome.

Interestingly, the 'business case' for the current roads programme includes an assumption that car occupancy is going to carry on falling. So a commitment to increase average car occupancy (see above) could potentially blow a big hole in the justification for that £27bn roads programme.

Still behind the curve

Despite these positives, my overall impression of the TDP is that ministers still want to assure the public that they can carry on driving, when the evidence clearly shows that this simply isn't compatible with the urgency of the climate crisis. In the aftermath of the pandemic and in the run-up to COP26, this feels like a huge missed opportunity for action not just to tackle the climate crisis but also the congestion, pollution, road danger, physical inactivity and transport inequality crises.

In this respect, the Government is lagging behind the Scottish and Welsh governments, not to mention the advice it is receiving from its statutory advisory body on climate change, and indeed the views of think-tanks from across the political spectrum. It is also lagging behind public opinion:

- The Scottish Government recently announced a target to reduce car-kilometres by 20% by 2030, while the Welsh Government’s recent Wales Transport Strategy aims to increase the proportion of trips made by walking, cycling or public transport from 32% in 2019 to 47% by 2040.

- The 6th Carbon Budget report from the Committee on Climate Change (CCC - the Government’s statutory advisors on decarbonisation) called for measures to reduce demand for car travel by 6% by 2030, increasing to 17% by 2050. Its more recent 2021 Progress Report to Parliament calls for funding “to be rebalanced away from cars…and towards public transport and walking and cycling”.

- Think-tanks ranging from IPPR to CEBR and Policy Exchange have all published reports calling for various forms of road pricing. The idea has also been backed by AA President Edmund King.

- The Climate Assembly, a demographically representative ‘citizens jury’, supported action to reduce road traffic levels in absolute terms.

- Recent polling by Ipsos MORI found that public support for urban road user charging has increased hugely over the past 13 years, from 33% in 2007 to 62% in 2020. Support is roughly equal among drivers and non-drivers, and is even higher among ‘captains of industry’. Public support rises higher still if the receipts are used to improve air quality or public transport, or to tackle climate change – whereas it falls sharply if they are simply returned to drivers in the form of lower vehicle taxes.

Given all this, it is high time the Government put in place clear evidence-based targets and pathways to decarbonise road transport (and indeed other transport), in line with its own 'net zero' commitment to decarbonise the wider economy, and to put in place the evidence-based policies (including road pricing) and the funding commitments that these targets will require,

It is not too late to do this. The TDP now feeds into a cross-Governmental 'Net Zero' review, being overseen by the Treasury. The question is whether Treasury ministers will finally agree with their transport colleagues to reallocate transport spending in the way that reflects the urgency of the climate crisis - while also tackling congestion, pollution, physical inactivity, road danger and transport inequality, and improving the economy and our quality of life while we're at it.