Great Rides: Pedalling to Panama

For years I dreamt of visiting Central America and particularly Nicaragua, but was deterred by a combination of civil wars and a steady job. In 2005 I finally broke loose from my steady job and took my bike to northern Mexico, from where I cycled 4,300 miles to the Panama Canal. I pick up the story in the tranquil town of Choluteca in Honduras, where I had spent two days waiting for a bank to liberate my debit card.

All uphill

From Choluteca there are two routes into Nicaragua. The direct route goes across the coastal plain towards León. This way, the frontier was 30 miles away. The road would be busy with commercial traffic. The alternative route goes inland through the mountains, crossing into Nicaragua near Somoto. It would be a lot quieter. The distance to the frontier this way was over forty miles, mostly uphill. I love mountains so I chose the latter route.

Not only was it uphill, there was a headwind and it was raining. It was like cycling up Glencoe. After fifteen miles of cycling hell, I approached a small truck that had stopped by the side of the road. The driver was filling his water bottle from a mountain stream. In the back sat four men in their twenties, each wearing a baseball cap and carrying a small bag. I stopped to fill my bottle, and the friendly driver asked me if I wanted a lift. “Five dollars” he said. I must admit I was tempted.

Climbing into the border mountains, I was aware that this area was used in the 1980’s by the Nicaraguan Contras and their United States “advisors” to train and launch raids across the border into Nicaragua, to fight the Sandanista government. I tried in vain to see evidence of past skirmishes, but the jungle quickly obliterates everything. It all looked peaceful and innocent.

I stopped just short of the border in the drizzle and slowly walked to the frontier post. This was supposed to be the dry season, and my waterproof jacket looked out of place in tropical Central America. It was useful though, as I needed all the pockets for the forms, ball-point pens, and more forms, needed to get into Nicaragua.

Getting through the border

The immigration offices were sleepy in the rain. There were hardly any other travellers, and I dealt with the formalities efficiently in a few minutes. Or so I thought. I freewheeled down to a chain dangling across the road, guarding the entrance to Nicaragua. A policeman asked to see my passport. Then he asked for the “paper” for the bike. I thought he was joking at first, but he was quite firm. I had to go back to the offices and get my bike documented.

Bureaucracy can be frustratingly irritating, but I knew I had to play the game their way. I went back to the office compound and pedalled round it a couple of times looking for signs of activity. It must have been tea-break. There was no one around apart from a handful of teenage boys, hoping to earn tips from people crossing the frontier by being helpful. They understood the frontier procedures perfectly – probably better than many frontier officials. I told them I needed a paper for the bike and they knew exactly which room I had to go into to get one. It was the Customs department.

I went in with my entourage of ‘all-purpose boys’ who were all doing their utmost to assist me. It felt good to be on the receiving end of competition. The customs official presided over a very old type-writer, one that went “clackety-clack” as he thumped the keys to make the metal letters stamp an imprint on the sheet of paper he had rolled into the machine. He had numerous questions, such a “value of bike”. I lied that I had bought it for only a few dollars. He wanted to see the receipt and I lied again that it was second hand, therefore no receipt.

Needing a licence plate

Then came his coup de grâce. “Licence plate number” he asked. “None” I said. “All bikes in Nicaragua have number-plates.” he retorted. I reminded him that it wasn’t a Nicaraguan bike, but he was reluctant to accept my word. One of the boys suggested lifting the bike up to see if the number was stamped underneath. Perhaps they had seen other British tourists with their postcode embossed into their bike frame. So I lifted my bike into the air, and the boys (who were all known to the Customs man) confirmed rather grandly “None!”. He believed them, thankfully, and issued me with my licence. My helpers had all been very pleasant so I gave them a handful of money to share, and freewheeled back down to the chain. The policeman saw me coming and dropped the chain onto the road for me. Finally, after years of wanting to be there, I was in Nicaragua! An ambition had at last come true, and I was singing at the top of my voice.

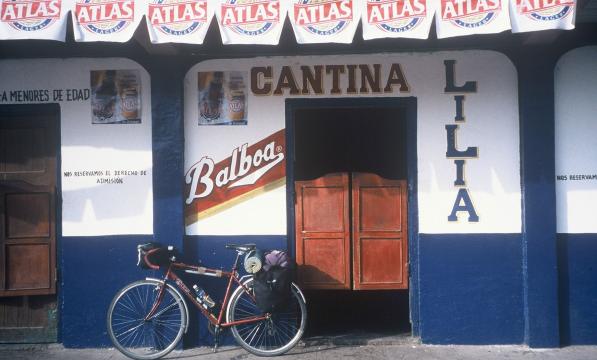

A hundred yards along the road was a two-storey whitewashed house; one of its front rooms was a shop. The gable end wall, in large proud letters, proclaimed “Welcome to Nicaragua”. I went in and bought a celebratory drink and some bananas. The family fussed over me as if I were royalty. I felt welcome indeed.

The road continued to the small town of Somoto. There was hardly any traffic and I pedalled along looking at the scenery, enjoying my sense of exhilaration at the very thought of being in Nicaragua. The hills were lush green and steamy in the rain, heightening my sense of history.

I stayed in Nicaragua a month before continuing through Costa Rica to Panama, finally crossing the bridge over the Panama Canal with a police escort, in April 2006.

Find the full story in his book: