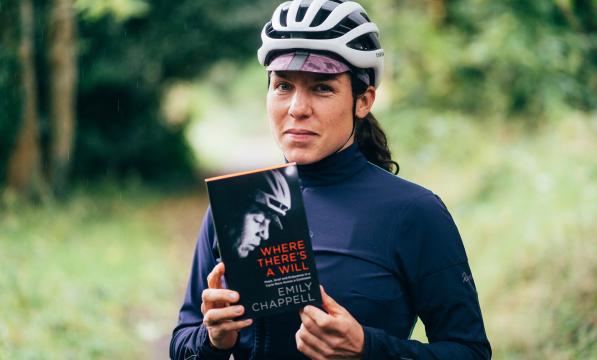

My 2020: Emily Chappell

“I’m so lucky,” I told myself, as I cycled through the bustling greenery and flowers of an unaccustomed English August. It wasn’t just that I was one of the people whom lockdown had blessed with time and space (rather than putting me in the impossible position of having to work full time and home educate my kids, as many of my friends were trying to do).

I was also grateful that my life already revolved round an activity that’s relatively safe in a pandemic – unlike those poor people who would normally spend their free time on a crowded football terrace, or in the pub, or at live concerts, or dancing the night away.

Cycling not only meant that I had a ready source of physical exercise and mental wellbeing – never more needed than now – it also gave me a place to go that felt safe and familiar, where I could pretend, just for a few hours, that none of this was happening.

Despite my good fortune, the first few months of the pandemic felt suffused with melancholy and loss – a feeling I eventually recognised as grief, though for me it was a subtler, more diffuse grief than that of losing a loved one.

I was in Edinburgh when I realised that the world as I knew it was ending, and that the only responsible thing to do was to get myself home to Bristol, and stay there. Awake too early for my 7am train, I pedalled slowly through the deserted streets, as the sun rose from behind Arthur’s Seat and glowed on the walls of the castle.

“I feel a strange sort of sadness,” I texted to a friend. “Like I’m saying goodbye to the world for a really long time, and it might not be the same when we come out of the bunker.”

For the last few years I’ve been travelling almost constantly, for races and press trips, to give talks and speak on panels, to run workshops and lead rides. Exhausting though it often is, I’ve loved it, and one of the many benefits has been getting to know the UK the way most people know their neighbourhood: finding shortcuts along its lanes and bridleways; nurturing friendships in its towns and cities.

I had Prince’s Street to myself that bright, ominous morning – unlike when I’d been Christmas shopping here as a child, or celebrated Hogmanay in my 20s, or ground to a triumphant halt at the Scott Monument after cycling up from London. Nothing would be the same after this, I melancholically told myself. My life of carefree travel was coming to an end.

The habit of being elsewhere was harder to kick than I’d expected. It was only now, grounded by a pandemic, that I began to settle into my new home

Emily Chappell

I arrived in Bristol that evening, wrestling with feelings of homecoming and claustrophobia. A glum procession of emails and phone calls had cancelled all my plans for the foreseeable future. Infections weren’t set to peak till late May. No one knew what lay ahead.

I took a deep breath, and settled myself back into my ultra-racing mindset. There is no point fixating on the finish line, I had decided during one of my earlier races, when it is so distant that reaching it seems not only impossible, but so far removed from the present situation that it belongs to a different story. And nor should I expect things to go to plan – or even make any plan firmer than a general intention.

Too much can change between the two ends of a continent for a rider to be able to predict and prepare with any useful accuracy. The best way to get through the miles ahead was to make sure I was always in the best possible shape to face the next challenge, be it something I had anticipated, like a long climb, or something unexpected like a crash, a mechanical or having to reroute.

During the first weeks of lockdown, I adapted my daily checklist from races. As well as asking myself if I’d eaten and drunk well, slept enough and stretched recently, I also made sure I was getting outside at least once a day, and having some sort of social contact, even if it was only a phone call.

April and May felt like the endless summer holidays I remembered from childhood – an expanse of time both daunting and luxurious. While I enjoyed reading novels and cooking elaborate meals, the part of me that needs to be busy and useful chafed against this enforced leisure.

Somewhere just beyond my warm sunny garden, the world was falling apart, and I wanted to be one of the ones helping to hold it together.

Cycling, that endlessly malleable pastime, stopped being my form of transport between cities, and became a tonic and an escape route. Friends in Italy and Spain were confined to their houses, and I thought about them as I raced along Wells Road each afternoon, heading for the hills and valleys south of Bristol, grateful I was still allowed outside.

A sense of social responsibility kept me from riding very long distances – what if I needed rescuing? At a time of year when I would normally be ramping up my mileage, in preparation for whatever challenge I had in mind for the summer, my rides rarely lasted beyond two hours. Quite often I’d finish with an ascent of Dundry Hill, and gaze at Wales on the horizon, wondering when I’d be allowed to ride there again.

For those first idyllic weeks, motorised traffic disappeared and cyclists briefly dominated the roads. Somerset’s lanes were the busiest I’d ever seen them, thrumming with a delightful medley of riders.

I waved at teenagers on mountain bikes, students on tourers, nervous-looking people on rusty hybrids, families in complex flotillas of tandems, tag-alongs and balance bikes, and people I recognised from social media, but had never met in person.

This had been one of my reasons for moving to Bristol from Wales, a year previously – of all the cities I knew, it seemed to be the one with the most cycling people. I knew it would do me good to stop travelling and spend more time in whatever place I called home.

But although I always looked forward to getting back to Bristol’s steep hills and brightly painted houses, the habit of being elsewhere was harder to kick than I’d expected. It was only now, grounded by a pandemic, that I began to settle into my new home.

I got to know the local roads so well I could leave the house without a plan, and improvise a route to suit my mood and energy. And, as the world began to open up again, I discovered that you’re never short of a riding buddy in Bristol, should you want one.

For this spinster cyclist it still feels like a wonderful novelty to gossip with a friend as we pedal along the bike path towards Bath – or to be invited to join a group of fast women who (lockdown-permitting) get together on Friday mornings, for a pre-work spin that always ends at a bakery.

By early June I would normally be at the peak of my fitness, having spent most of May recce-ing the Tour de France route, in preparation for leading Le Loop. It was unsettling this year to realise that I hadn’t cycled more than 200km since… I couldn’t remember when. What if suddenly I woke up and this had all been a bad dream? I was nowhere near ready.

The commitments I’ve formed in Bristol mean I’ll spend less time elsewhere – just as I realise how much of my soul resides in the French mountains

Emily Chappell

And I missed France like a lost limb. I didn’t know, until it was taken away, how much Europe and its roads and mountains had become part of my summers. Now, like a person you long for, I saw it everywhere.

A village in the Mendips reminded me of the Massif Central. Quirks of junctions and hedgerows took me back to Brittany and the Rhône Valley. I lost track of myself on a ride through Wiltshire, and became convinced I was in the Pyrenees.

Eventually I found myself riding long distances again. This was partly because my yearnings for usefulness had come to fruition and I had found a way to serve my community that now kept me busy several days a week – meaning that I had to squeeze my miles into a few big rides, rather than many smaller ones. And other riders seemed to be on the same wavelength.

I rode a lumpy 300k with Audax impresario Will Pomeroy, and in September covered 600k with five other Bristolians, enjoying ourselves so much that it felt more like a holiday than an athletic undertaking. I discovered that another TCR winner lived just round the corner from me, and we started swapping routes and beasting each other around the Mendips.

By October I was as strong as I’d ever been going into winter, but without the accumulated fatigue of riding 4,000km in August, as I usually do.

I’m now daring to hope that this pandemic really will come to an end, and that next year will take on a more familiar shape for me. But some things have changed forever. I feel more at home than I have for a long time, but the commitments I’ve formed in Bristol mean I’ll spend less time elsewhere – just as I realise how much of my soul resides in the French mountains.

I’ve affirmed my great fortune in having a life that revolves around cycling – while simultaneously realising how much more useful I’d be to the world if I did something else. And I’ve learned, yet again, to take nothing for granted.