Great Rides: Isle of Wight by gravel bike

Within a few minutes of leaving Ryde Pier, we had left the tarmac and I had no idea where I was.

I had been to the Isle of Wight before. A couple of years ago I had found myself in Southampton with a free day, taken the ferry across to Cowes, and pedalled 100km or so around the perimeter of this tiny, temperate island. It was a pleasant way to spend a few hours, but it hadn’t occurred to me to go back.

But then I was grounded by lockdown. By October, I’d normally have cycled thousands of miles on foreign soil, crossed borders and skirted coastlines, and discovered forests and mountains and remote gravel tracks I didn’t know existed. My unfulfilled yearning for travel – a very specific mixture of homesickness and wanderlust – was a nice problem to have, compared to what many were going through, but it was still a problem.

So when Tim Wiggins said he wanted to show off his local gravel, and when I realised I could manage the whole trip as a day return, with no need to set foot indoors, I jumped at the chance. I got up at five, snoozed through my first train journey in six months, and woke up to sunrise over the Solent.

And as I pedalled through the autumn leaves, branches meeting above my head, and sunlight flickering over the riders ahead of me, I knew I’d made the right decision. A sunny day this late in the year is always a blessing, and this one came with the added piquancy of a brief respite from lockdown. For now, it was possible for me to travel here from my home in Bristol, but I no longer took for granted that this would last.

Wheeling my bike onto the FastCat in Portsmouth carried the memories of dozens of other ferries I’ve taken, across the Channel, and between the islands and coastal cities of the Mediterranean. This was the closest I could get to being abroad, whilst sticking to the foreign travel ban I had imposed on myself. And this tiny island, unfamiliar as it was to me, felt suffused with the sense of mystery and adventure that I’d usually feel as I piloted my bicycle through some as-yet-undiscovered region of Europe.

We had ridden for less than 5km along our dappled bridleway, when an enormous building appeared on our right, somehow combining the austerity of Belgium with the flourishes of Constantinople. This was Quarr Abbey, constructed of Flemish brick on the site of an older Cistercian monastery, and (unbeknownst to me) one of the most important 20th-century religious buildings in the UK. Tim told us how the monks – like the more famous Trappists – had previously been known for the beer they brewed. Nowadays their kitchen garden supplies an on-site teashop, but it was too soon to stop, so we sped off, heading inland on a firm doubletrack byway. Cathedrals of beech trees vaulted above us, and now and then we emerged briefly to cross a main road, then disappeared from the world again. Aside from a few dog walkers in the first kilometres, we had passed no one.

Local lads Tim and James told us how crowded the island gets in the warmer months, and how, with a brief respite for the first two months of lockdown, this had been one of the busiest summers in living memory. I recalled the congested roads and impatient traffic of my last visit, and we all confirmed our smugness at having found a quieter way to see the place.

“We actually have a higher density of public bridleways here than anywhere else in the UK,” explained Tim.

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“I’m not sure exactly,” he admitted. “Something to do with it being an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, so they’ve not been able to develop it much. And historically it’s always had lots of small farms, rather than a few big ones, so there are more tracks joining them all up.”

We carried on, peering curiously along the trails that bisected our route. The journey had seemed gentle and flat thus far, but I became increasingly aware that I was working hard, and occasionally having to push to keep up with my riding buddies.

Eventually the trees opened out and a distant horizon appeared – rolling hills with the promise of a sea view – and it became clear that we were gaining height. This was confirmed a few minutes later, as Tim swung abruptly left into some bushes, and led us down a raucous singletrack descent, close to the limit of our tyres and comfort zones, but also the point of the ride at which my heart really began to sing. By now the day felt more like early summer than late autumn, I had stripped down to a baselayer, and we were all glad we had chosen to spend this Friday on our bikes, rather than at our desks.

Tim had promised us a coffee break in Niton, but none of us could resist stopping once again as we skirted an unexpected meadow in full bloom. The boys waded in to photograph sunflowers and cornflowers, and I marvelled at how summer seemed to be clinging on here, knowing that the leaves would already be on the ground a few hours north.

Our coffee stop did not disappoint. The Norris family grocers in Niton sells the biggest fondant fancies I have ever seen, so we stocked up on coffee and cake, and repaired to some nearby benches to reduce our bounty to a packable quantity, as we compared notes on other gravel hotspots, and waved at passing road cyclists, on their own loop of the island.

We joined them on the tarmac briefly, before veering onto an extraordinarily steep track that whisked us straight up to the brow of the hill, where we paused to catch our breath, gaze out at the vast blue sea and the Needles in the distance, and listen to Tim’s account of how the amusement park down the hill at Blackgang had gradually shrunk over the years, as the cliffs crumbled into the sea.

All pretence of a road evaporated further up the hill, and we bounced over tight coastal grass towards a tall stone structure that most resembled a child’s drawing of a spaceship. This was St Catherine’s Oratory, Britain’s only surviving medieval lighthouse, and the high point of our ride. We had been promised lunch at The Garlic Farm, but no one was in a hurry to leave this place. Long before the lighthouse was built in the fourteenth century, prehistoric inhabitants buried their dead here, and I marvelled at the spiritual compulsion I seem to share with our ancestors – to find sacredness in summits and wide-open spaces.

We plunged off the side of the hill, whooping our way back into the island’s interior of farmland, ancient cottages, and meandering gravel tracks.

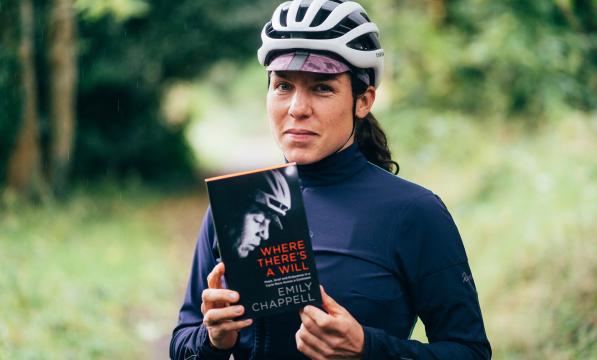

Emily Chappell

We plunged off the side of the hill, whooping our way back into the island’s interior of farmland, ancient cottages, and meandering gravel tracks. For an hour or so we sat in a sunny garden, stuffing our faces with garlic-scented chips as chickens and peacocks strutted around us. And then we hiccupped our way along the traffic-free Red Squirrel Trail to the coast, nodding our hellos at dog walkers and families on bikes, and sharing their glee at having managed to be outside on what might well have been the last warm day of the year.

Tim had been optimistic about getting us back to Ryde for the 16.47 ferry, but it was after three by the time we left the Garlic Farm, and the full blaze of the October light was fading to a blush as the sun slipped behind thin clouds on the western horizon. As we struggled upwards, onto the cliffs that overlooked the broad sweep of Sandown Bay, the sky and sea seemed to coalesce into a quiet, dusty blue, and we dawdled, knowing that this moment – this whole day – was ephemeral, and that the only way we had of holding onto it was to pause, and drink it in for as long as we could, while it lasted.

We circled Culver Battery, remembering that this edge-of-the-world coastline has always had strategic, as well as spiritual significance, and that the vast blue distance that lay beyond us has, at various points in its history, harboured the threat of annihilation as well as the promise of salvation. And then, for the last time, we launched ourselves down the side of the hill, hoisted our bikes over a stile, and found ourselves back on the tarmac, for a final sprint along the seafront, and a hasty farewell at Ryde Pier.

Within an hour I was back on the train, masked and sanitised, regarding my muddy legs and muddier bike, and yawning with the satisfaction of a day well spent, and a night in my own bed at the end of it. I still miss meandering around Europe, but as silver linings go, the Isle of Wight isn’t half bad.